Alice Wong

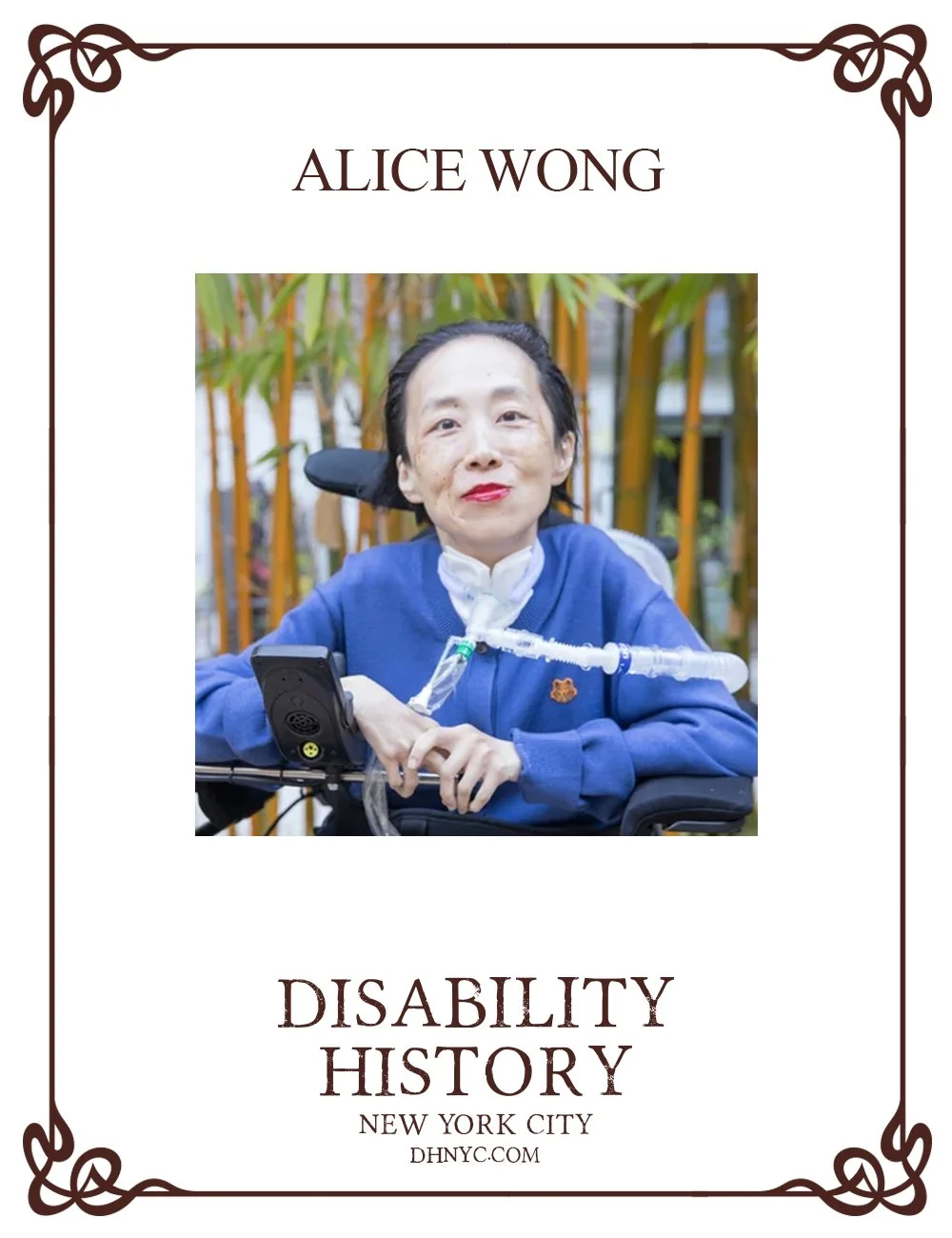

In image No. 1: A photograph of Alice Wong.

One of the most compelling and influential disability voices of our time, Alice Wong, passed away in November, 2025. She was 51 years old.

Wong grew up the daughter of immigrants from Hong Kong, in the suburbs of Indianapolis. Born with spinal muscular atrophy, a progressive neuromuscular disorder, as a child Wong gravitated to science fiction and literature, because she found allies and role models in characters like the X-Men’s Charles Xavier. Wong later described herself, with her trademark wry wit, as a “nerd of color.” In an autobiographical essay, “A Mutant From Planet Cripton,” Wong summed up her life’s mission by writing, in the third person, that “‘Alice,’ her Earth name, embraced her identity and found power in the community of fellow Crips around her. Scrutinized and labeled deviant by the Authorities, Alice and her Siblings of Cripton continue to fight for social justice and equality for mutants and non-mutants alike.”

Wong became best known for boosting the voices of other people in the disability community. A principal vehicle was the Disability Visibility Project which, in partnership with StoryCorps, collected oral histories from at least 140 people. The project eventually incorporated a podcast, and maintains a very active online presence, at disabilityvisibilityproject.com .

As that community grew, it took on political engagement under the hashtag #CripTheVote, which hosted Twitter town halls with figures like Senator Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg. Other collaborations included #CripLit and, in the wake of Donald Trump’s election as President in 2016, Wong assembled an anthology of essays entitled Resistance and Hope. Other collections followed, including her best-known work, Disability Visibility: First Person Essays From The Twenty-First Century, published in 2020.

A successor anthology, Disability Intimacy: Essays on Love, Care, and Desire, appeared in 2024. By then Wong had published a best-selling memoir, Year of the Tiger: An Activist's Life, and had become something of a pop culture figure, to the point that she played a fictionalized version of herself on the Netflix animated series Human Resources.

Wong’s outreach to young people included a young readers’ edition of Disability Visibility, and a column in Teen Vogue magazine. She brought Asian American and Pacific Islander voices into the disability movement. In 2013 Wong became an Obama presidential appointee to the National Council on Disability, and in 2024 she was named a MacArthur Fellow—the so-called “genius grant.”

Because of her disability-related service requirements, she was a nearly lifelong recipient of Medicaid, which she described as a “life-giving program.” Wong nonetheless wrote that “death is an intimate shadow partner.” But nothing interfered with her determination, as NPR put it, to live “an unapologetic, unabashed disabled life filled with science-fiction, good food, and cats.” WQED quoted her as saying “Being able to use my privilege to pass on opportunities to other disabled people and support projects I believe in brings me so much joy. We live in such bleak times and what keeps me going is living to the maximum without apology.”

As her medical situation progressed, Wong began communicating through digital text-to-speech. True to her nerd roots, she took to describing herself as a “disabled cyborg.” That blend of unflinching humor, vulnerability, and radicalism persisted right to the end. In a dying declaration posted by her friend and colleague, Sandy Ho, Wong wrote “Hi everyone, it looks like I ran out of time . . . You all, we all, deserve the everything and more in such a hostile, ableist environment. . . I’m honored to be your ancestor. . .

“Don’t let the bastards grind you down.”

Note: a version of this entry appeared in Able News, ablenews.com

by Warren Shaw