Vincent Marchiselli

In December 2013 the journalist Sam Roberts published an obituary for Vincent Marchiselli. Its basic thrust went something like this:

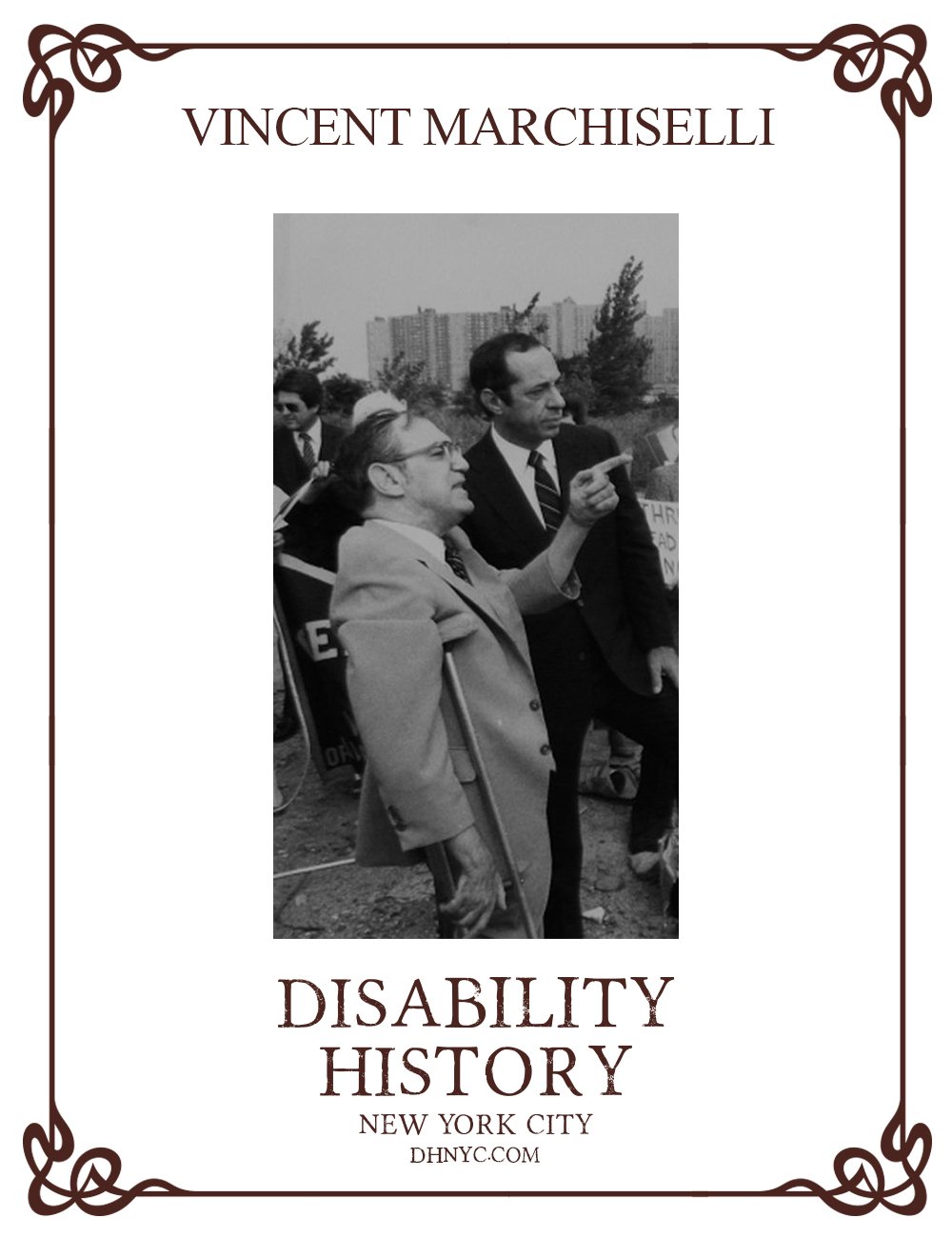

In Image No. 1, Vincent Marchiselli on the left, with Governor Mario Cuomo on the right, circa 1988.

Vincent Marchiselli was a member of the New York State Assembly, representing the Edenwald and Gun Hill sections of the Bronx. First elected in 1974, he is best remembered for his stance against the corruption that plagued the Bronx Democratic Party in the 1980s and eventually brought down its boss, Stanley Friedman (after a trial prosecuted by then-US Attorney Rudy Giuliani). The voters did not reward Marchiselli’s independence—after his district was reapportioned, he lost reelection in 1984. Despite several attempts, he never again held elected office. He passed away in 2013, at age 85.

By any measure, that’s the record of a notable life. But there is an entirely different way to tell Vincent’s story, and it goes like this:

Vincent was one of the founders of disability activism in New York City. He was responsible for the very first legal protections for the civil rights of people with disabilities. Significantly disabled by polio, a user of crutches and a wheelchair, Vincent built a decades-long career as a political advisor, activist and elected official, all the while maintaining the family business—running a funeral home.

I doubt he’s well remembered today, but Vincent’s unlikely journey, and his pioneering path, deserve wider recognition.

Vincent Marchiselli (pronounced “mark,” not “march”) was born in 1928 in the Bronx, and contracted polio in 1931. After a lengthy hospital stay followed by a series of corrective surgeries a few years later, the young Vincent was ready for an education. Public school was only available for kids who could get on and off the schoolbus by themselves, a feat that Vincent, then exclusively a wheelchair user, couldn’t manage. But through his father slipping five bucks a month to the bus driver, a second wheelchair kept at the school, and another five bucks a month to the school’s elevator operator, Vincent was able to get a regular education.

At age 15, Vincent both managed ambulation with crutches and completed high school. Graduation was followed by surgeries to his wrists and thumbs. During his convalescence, he was amazed to receive a visit from baseball hero Joe Di Maggio, like Vincent a Bronx native of Italian extraction. After graduation Vincent enrolled at Iona College, where his social abilities and leadership showed themselves. Vincent was elected Vice President of the student council and, perhaps more remarkably still, he became an athlete—the coxswain or steersman for the school’s boat racing team. As Vincent explained it to me, he was “the guy who sits up in the bow, with a megaphone, and faces the oarsmen who sit backwards, and he calls out the cadence to the rowers. That was a new experience!”

Meanwhile, Vincent’s father, a mailman turned funeral home proprietor, had gotten involved in Bronx politics.

The Bronx was politically unique. It had a both a potent heritage of activism and a durable party machine. Influenced by his father’s experience (he ran for District Leader three times, but was blocked by party regulars), Vincent jumped in, picking the lane of a moderate reformer not tied to the organization.

In fairly short order Vincent became campaign manager for a former Assemblyman who was angling to regain his seat. He did well enough to get hired in the same capacity for three or four other Assembly races. By 1959 he was President of the North Bronx Democratic Club.

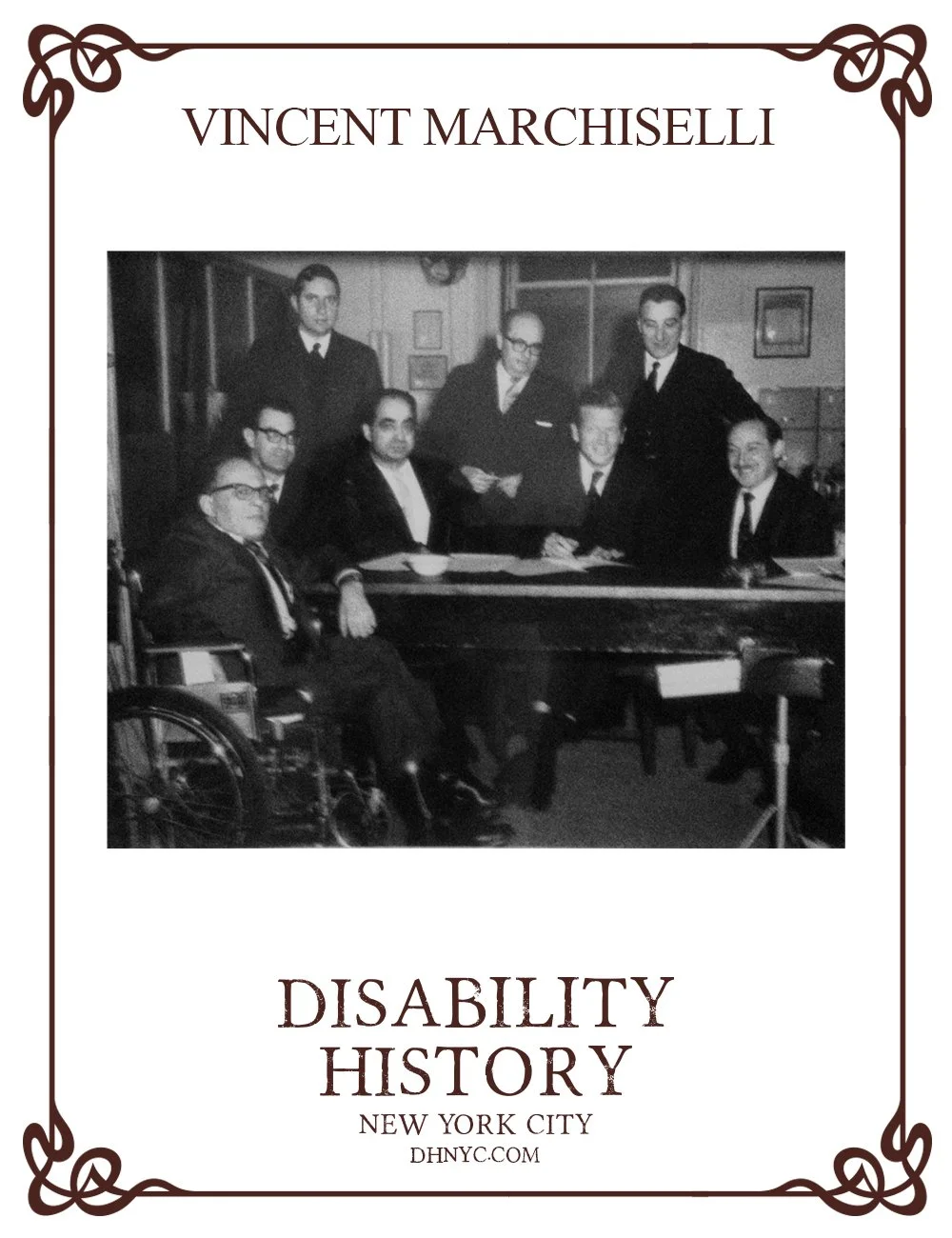

In Image No. 2, a photo dated December 23, 1968, showing Mayor John Lindsay signing into law an amendment to City’s Human Rights Law, which for the first time ever barred discrimination against people with disabilities. From left to right: Julius Shaw, Vincent Marchiselli, unidentified, Mario Merola, Joel Tyler, Mayor Lindsay, Dr. Howard Rusk, City Council Majority Leader David Ross.

Soon he was Board chair of the Bronx County Civic Association, and was engaged to a social worker from Manhattan, Eunice Pavia. Armed with a master’s degree from NYU, his father’s successor as funeral home proprietor, and a seasoned political figure, Vincent was taking liberal public positions on issues like gun control, real property tax breaks for the elderly, and air pollution control.

Mobilization for Maturity was one of the organizations that emerged from this activity. Founded by Vincent in 1964 as a self-help group for disabled and elderly Bronxites, it had some 150 members.

Vincent had not been generally involved in disability activism. He was at the time unaware, he told me, of the free parking at meters campaign that ran from 1961 to 1966. The turning point was Mayor John Lindsay’s towaway plan of January 1967—an effort to clear traffic congestion in midtown by prohibiting most parking and towing away parked cars, including cars owned by people with disabilities (even though they had no other means of travel at the time). Vincent denounced the plan as a “cockamamie, insane idea.” He was so incensed that he agreed to become the named plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging the policy.

Marchiselli v. Lindsay went nowhere—the judge refused to sign the papers (an Order to Show Cause against the Mayor), and that was that.

But disability rights remained on his radar. Through a colleague, Councilmember Mario Merola, Vincent succeeded in introducing an amendment to the City’s Human Rights Law, to add disability to the classes of people protected against discrimination in employment, housing, education, and recreation. After a lengthy fight (which included opposition from the Human Rights Commission itself), Mayor Lindsay signed the amendment into law on December 23, 1968.

This was legal protection without precedent in human history so far as I am aware, a great triumph for Vincent and the Bronx Democratic leadership that had backed the bill.

Among other things, the amendment was notable for its definition of a person with a disability as someone who relied upon a device, appliance or seeing-eye dog in the performance of “daily responsibilities as a self-sufficient, productive and complete human being.” This remarkable phrase, Vincent later told me, was suggested by his wife.

In 1973, having assisted in many elections on behalf of a dozen or more candidates, Vincent decided to try the game himself, and in 1974 he took office as a member of the New York State Assembly. He had run on mainstream issues like subway crime, air pollution, and public ethics, and he continued in that vein. As Chair of the Election Law Committee, and later as Majority Whip, Vincent had enough clout to win funding for local projects, and to defeat a proposal to turn an MTA bus depot in Baychester into what many suspected was slated to become a toxic waste dump.

Disability rights remained in his wheelhouse. Vincent was one of the prime movers behind a 1981 event in which members of the Assembly donned blindfolds and took to wheelchairs for several days, in order to acquire, even briefly, first-hand experience with disability. I have little doubt that Vincent played a behind the scenes role in the 1974 amendment of the State Human Rights Law to cover people with disabilities. And he was one of a select group of Democratic convention delegates with disabilities who supported Ted Kennedy’s bid for President in 1980.

Through it all, Vincent remained a moderate. But as the public agenda evolved, some of his once solidly majoritarian positions came to seem conservative. As a practicing Catholic, for example, he was opposed to what was then known as gay rights. He was also an opponent of abortion rights but--with a consistency rare in public officials--he was also opposed to capital punishment, because government should not deal in lives.

Thanks to my parents’ activism, I almost certainly met Vincent when I was a boy, and I certainly heard his name a lot growing up. I got the chance to interview him in 2011. We spent a few hours together at an IHOP in the Bronx. At more than eighty years old, Vincent was friendly, quietly authoritative, an elderly gentleman of Italian stock, and a compelling storyteller. We had a lovely brunch, and parted promising a repeat, but as so often happens, that repeat meeting never took place.

Vincent died in 2013. So I didn’t know him well. But he was among the founders of the New York City Disability Rights Movement, one of the first visibly disabled elected officials, and a principled politician. He deserves our admiration, and a place in our collective memory.

Note: A version of this entry appeared in Able News, https://ablenews.com/

by Warren Shaw