THE FIRST DISABILITY PRIDE MONTH

Ten years ago, 2015, marked a round quarter-century since passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. It was an ideal occasion for some major events, and as early as January there were meetings and discussions about holding a Disability Pride Parade that July—and maybe even mounting a museum exhibition about the disability rights movement.

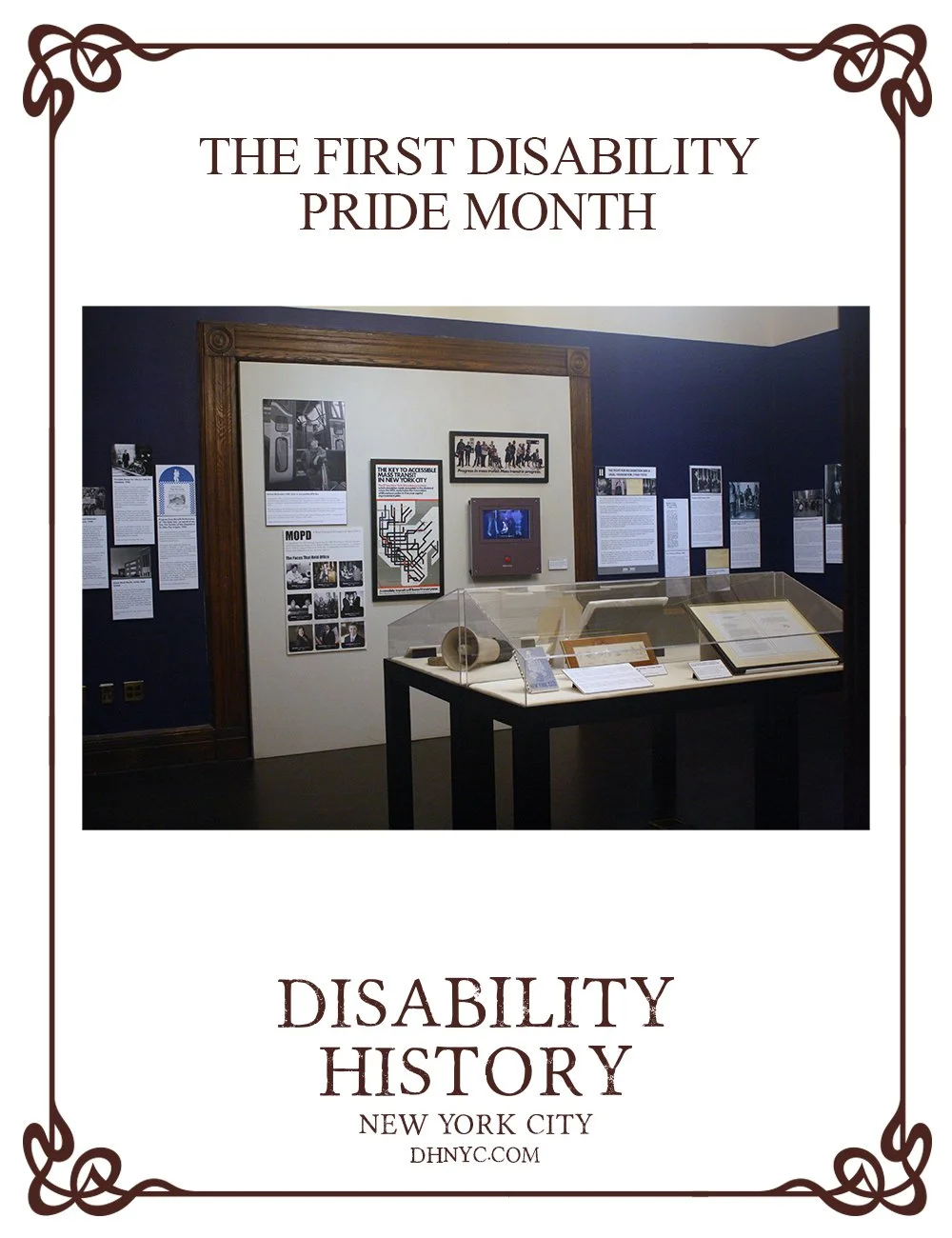

In Image No. 1 – A photo of the 2015 “Gaining Access” exhibit, courtesy of the Brooklyn Historical Society.

I was involved in these discussions. The parade proposal moved ahead, but not too much happened with the museum idea. I was unusually busy that spring, both in my law practice and with drafting a huge expert witness report for the Department of Justice, so the museum exhibit fell off my radar. Until April, when the redoubtable Carr Massi and Kleo King of the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities reached out to me.

Mayor Bill DeBlasio had declared that from now on July was going to be Disability Pride Month in New York City. Not only was the museum show a go, they told me, but the exhibit was going to open July first, and it was going to be the kickoff for an entire month of events and celebrations! MOPD even had a budget to make it happen.

After a few days’ discussions, I was absolutely thrilled to be named curator of the very first museum exhibit on our movement. After years of toiling in the City’s disability history, it was Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa and the Fourth of July all rolled into one!

Getting a museum exhibit from concept to opening usually takes a year or more. But this show was going to open July 1, so we only had about twelve weeks. And we didn’t even have a venue yet.

I drafted a proposal, which we shopped around to several museums. By the end of April we’d reached a tentative deal with the Brooklyn Historical Society. They offered us an entire gallery, with wall space for 30-40 pieces plus niches for some larger works, and enough floor area to hold a few display cases.

I prepared an outline, with section headings and text. To help with developing content, I volunteered every image, object and video in my possession, and MOPD and I began knocking on doors. We reached out to Disabled in Action, United Spinal, CIDNY, BCID, Able News, Jim Estrin at the New York Times, Luda Demikhovskaya, Jim Weisman, Phil Bennett, Marvin Wasserman and everyone else we knew. Carr Massi was indispensable, thanks to her firsthand knowledge and her unparalleled collection of movement ephemera, painstakingly gathered over decades. By the end of May we had hundreds of images to choose from. The next step was culling and creating a narrative.

I whittled the selections down to fifty or so (not including objects, video compilations and some other items, which would fill out the balance of the exhibit). I laid out a stack of blurry thumbnail prints on the floor of my living room and spent a few days playing with them, until I’d settled on the content and flow for the show. MOPD put in a huge amount of time getting the exhibition rights, and working with the Brooklyn Historical Society to improve accessibility at its building. For me, the big tasks were nailing down the dates and places and identities of the people depicted in each image, and drafting detailed text blocks for each section and each work—all of which had to be reviewed by Carr, MOPD, and the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Picking a name for the exhibit took quite some time, but in the end we agreed on then-MOPD Commissioner Victor Calise’s suggestion, “Gaining Access.”

The Museum handled most of the exhibit design, while MOPD saw to printing and mounting and transporting everything. Plans for the opening gala on July 1 began taking shape, highlighted by an understanding that the City’s First Lady would deliver the keynote address.

By this point, between practicing law, my federal expert witness work, and curating and prepping the show, I was too exhausted to write my own speech. But a day and a half upstate at an ashram, meditating and taking ayurvedic meals, restored me sufficiently that by a few days before the opening I had an address that I was happy with.

The exhibit was ready. The Museum’s designer had done a fabulous job. The section headings and text floated above the many images that illustrated the main themes. They maintained a generally even line around the room, punctuated by banners from United Spinal’s campaign for accessible mass transit, and a huge photo of Denise McQuade during her famous 1981 sit-in on a City bus.

On a video screen played a loop of moments from protests, performance excerpts from the Disabled in Action Singers, and a series of photographs from Jim Estrin at the Times, which illustrated the diversity and vitality of the City’s disability community. Display cases artfully showcased precious relics, like the megaphone that my parents brought to the huge Gas Rationing demonstration in 1974. Audio captioning was available via bluetooth.

Floating inside the gallery’s navy blue walls, pristine and glittering under the lights, the exhibit was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.

On the day of the gala I entered the Brooklyn Historical Society’s grand first floor hall, festively decorated for this unprecedented event, the first-ever museum exhibit on the New York City Disability Rights Movement. The First Lady’s attendance had fallen through, but there were dignitaries aplenty. Commissioner Calise gave a rousing talk, and so did Carr. My own presentation went over well, and when it was done I looked around. The hall was filled with colleagues, allies, friends, family, and people I hadn’t seen in years. All there to see my show. Unbelievable. Feeling like a Barnum or a Ziegfeld, I helped lead the crowd upstairs and unveiled the exhibit.

The first Disability Pride Month had begun.

Note: a version of this entry appeared in Able News, ablenews.com

by Warren Shaw