May Darrach

In Image No. 1: Indistinct photo from a 1902 newspaper, showing an adult white woman, light hair pulled back, wearing a high-collar, dark top.

May Darrach is very possibly the single most important person in the history of the American disability rights movement. Yet she is completely forgotten.

Born in 1869, in New Jersey, little May fell ill not long after birth, and was diagnosed with a condition variously known as Pott’s Disease, spinal caries, or spinal tuberculosis, in which tuberculosis invades the vertebrae and eats away at the bones from the inside out. Spinal degeneration or even collapse can eventually follow, and before the development of effective chemotherapy, Pott’s Disease often meant chronic pain, hunchback, paralysis, a painful wasting away and early death.

It seems likely that there were then many thousands of New Yorkers struggling with this condition. But little May Darrach was an exceptional case, from a remarkable family of ministers and physicians. Her uncle Bartow had been surgeon general for the Third Army Corps in General Sherman’s Division (he perished at the Battle of Vicksburg). Her grand-uncle William Darrach was a most eminent doctor, who ran the medical facilities at the Eastern State Penitentiary of Pennsylvania, the keystone state’s equivalent of New York’s Sing Sing. The crucial point is that the Darrachs rallied around the stricken little girl instead of being ashamed of her, as families then so often were. They used their ties to the medical community and saw to it that only the most highly reputed doctors tended to her. When the very limited state of existing medical protocol became clear to them, the Darrachs put their originality to good use. May’s uncle Marshall (another physician) devised a restraining jacket made of celluloid or hard leather, meant to painlessly immobilize his niece and, hopefully, restrain the growing deformation of her spine. The so-called “Darrach jacket” became something of a medical sensation. Other doctors claimed authorship of the device, and it inspired Lewis Sayre at Bellevue to develop an adaptation, a custom-built application made of plaster of paris, which was used for the next fifty years and more, under the name the “Sayre jacket.” It was used on my father, Julie Shaw, around 1937.

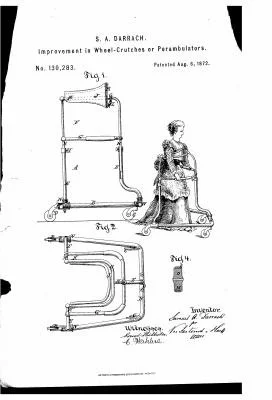

Not to be outdone, in 1872 May’s father Samuel, an inventor, patented a device that he called a “wheeled crutch.” It was a prototypical walker fitted with perambulator wheels and a chest or head extension, devised to allow his severely ill little girl, then three years old, to stand and even ambulate without putting pressure on her spine.

May was unable to walk unaided until she was thirteen. Although there do not appear to be any detailed descriptions of her condition, it is clear that she was visibly, even obviously disabled.

The support of Darrach’s family must not be discounted. Even today people who became disabled as youngsters tell me that it is almost impossible to build a successful life without the steadfast support of their family, or at least one parent. The same was true for this family, with its state-of-the-art disabled daughter.

Instead of the retiring, private life that was to be expected of a respectable disabled woman, Darrach put herself to work. Largely self-taught to this point in her life, she now spent a year at a school in Canada, then trained in the then-new kindergarten movement, preparing herself to be a childhood educator. In 1896, however, at the age of twenty seven or so, Darrach’s disability put her into the hospital. It was hardly her first time in-patient. But from this particular hospital stay she emerged forever altered, charged with a mission to do something tangible for what she (and everyone else) then referred to as “crippled children.”

In Image No. 2: the patent art for Samuel Darrach’s “wheeled crutch.”

After being released from the hospital, Darrach helped organize a new project—the Guild for Crippled Children of the Poor. The Guild’s statement of purpose reflected Darrach’s ties to the faith community: “to secure the cooperation of churches of all denominations and of societies in helping the poor to an intelligent care for their crippled children who are not otherwise provided for.” Displaying a talent for networking, Darrach’s new organization quickly attracted well-known figures as officers and Board members, including the pioneering photojournalist and social reformer Jacob Riis.

The turning point came when Darrach caught the attention of Charles Loring Brace, Secretary of the Children’s Aid Society. Darrach wagered CAS Secretary Brace that there were hundreds of disabled children hidden away in the poor parts of town, unreached by school, church, or any other outside influence. He was dubious, but Darrach knew they were there--she’d shared hospital wards with them. Now she slogged through the tenements and documented them. As far as I know, this was the first survey of disability in the general population. She presented her findings to Secretary Brace, and made her pitch.

Darrach must have been most persuasive, for Brace became an officer of the new Guild for Crippled Children. Because CAS was then one of the largest and most important child welfare organizations, Brace’s endorsement was an inestimable boost. Even more important, he agreed to take concrete action. The results both made Darrach’s reputation and set into motion the next phase of what I call the Dickensian Disability Movement.

The Henrietta Industrial School, at 224 West 63rd Street, was a roomy four-story building owned and operated by CAS for the poor children of “San Juan Hill,” then a largely Irish neighborhood located west of Columbus Circle. At Secretary Brace’s direction, by 1898 several rooms at Henrietta had been renovated and set aside for the instruction of disabled children.

Through CAS, Darrach had created the nation’s very first educational program for children with disabilities. It wasn’t long before she had company. By 1903 there were four schools. The Board of Ed jumped in in 1905, and by 1908 the New York Times proclaimed that the City led the nation when it came to schooling for children with disabilities.

By any measure, May Darrach’s campaign had really taken off. And she made the most of her opportunity. As early as 1900 Darrach had raised an endowment sufficient to found her own entity, the Darrach Settlement Home for Crippled Children. Located at the northern end of San Juan Hill, on West 69th Street, the Settlement Home was a fifteen- or twenty-bed facility. Like Henrietta, it provided a combination of education, medical care, skills training, social work and trips to the country. Unlike the schools, however, the Darrach Home provided beds, room and board—shelter—for children who had been abandoned, or were too acutely disabled to live with their families.

As if all this were not enough, Darrach somehow found time to attend the Women’s Medical College on Madison Avenue, and in 1904 she became a physician. Soon Darrach was running her settlement house, continuing her fundraising, pushing and prodding, giving frequent lectures (topics included the prevention of childhood deformity, among other things), all while practicing medicine at a suite in “The Severn,” a fancy new apartment building at Broadway and 73rd Street.

Doctor May Darrach was disabled, yet she was far too formidable to be ignored. A unique figure in the United States, Darrach was the first disability activist.

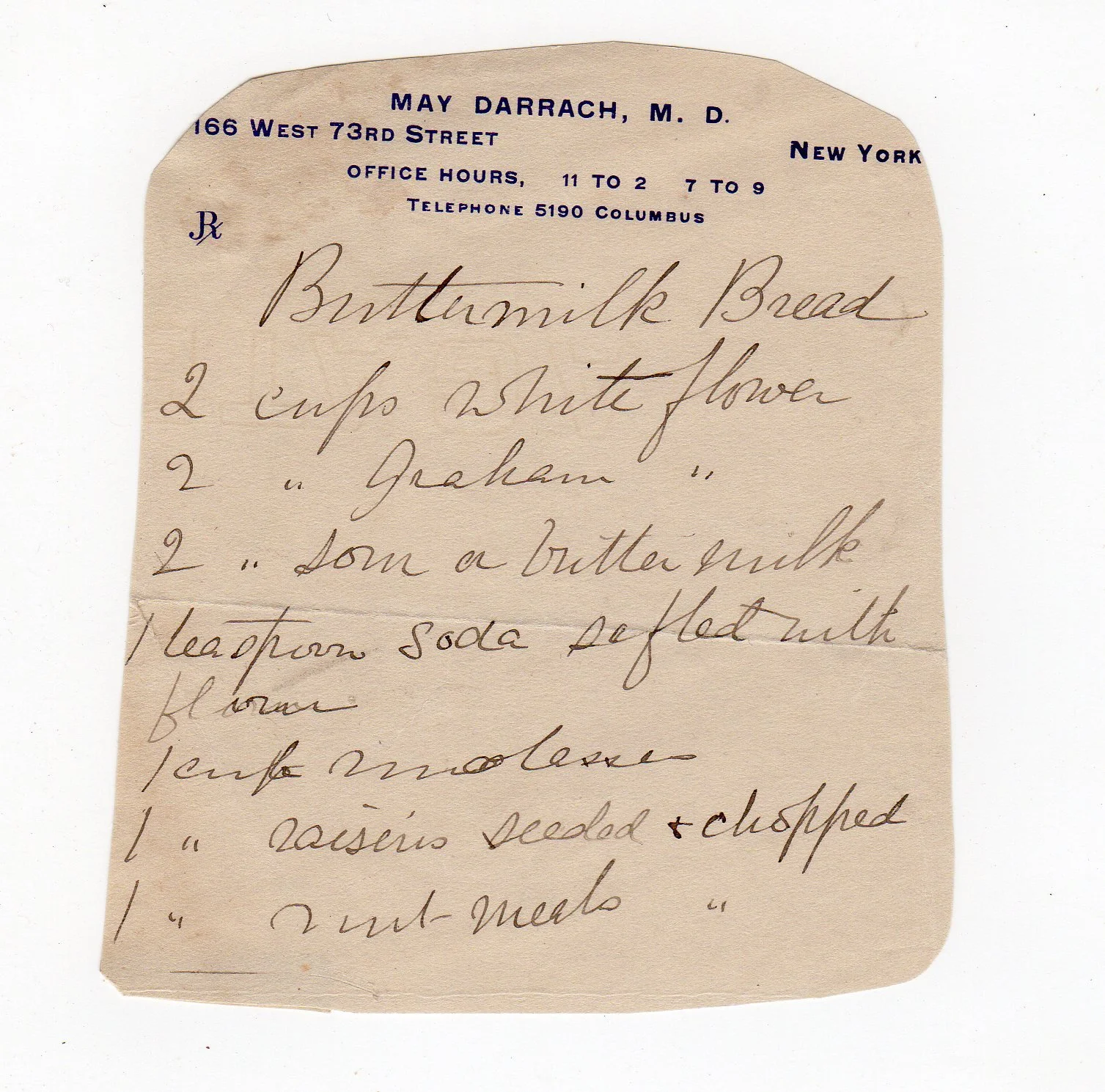

In Image No. 3: May Darrach’s recipe for buttermilk bread with raisins.

And she must have been very, very good, because under her influence new charitable efforts arose in increasing numbers--the Association for the Aid of Crippled Children, the East Side Free School, and many more, all built on the model of privately-funded philanthropy led by small groups of elite college educated Protestant women--an entire movement, in fact, targeted to disability in the general population, the first of its kind in the nation’s history. A number of these organizations survive to this day, and since many of our movement’s leaders grew up under their influence, it is fair to say that the consequences of Darrach’s work continue right down to the present.

To make all this happen, Darrach pushed herself unceasingly--past the point of no return. In 1910 her health broke down, and she was forced to retire. She passed away a few years later, at the age of forty nine.

Over a comparatively brief career of less than fifteen years, Dr. May Darrach achieved an impact which surpassed anything she could have reasonably expected. Yet she was seemingly devoid of ego, and made little or no show for herself. There is no evidence that she sought fame or personal attention, or even took a salary. My repeated searches have yielded just one photo of her, from 1902—and the newspaper caption fails to give Darrach’s name.

It is unclear whether she had much of a personal life. The only behind-the-scenes artifact is a recipe for buttermilk bread with raisins, written on her physician’s letterhead. The recipe is for a large loaf, but since she never married and had no children, who she baked it for is unclear. Like a Victorian tale of self-sacrificing womanhood, all she did was for her cause, and not herself.

Predictably, then, Darrach never got her due. More than one contemporary telling of the rise of the children with disabilities’ charity movement states that it was “begun by a woman who was herself a cripple,” but neglects to identify who that person was, or recount any portion of her remarkable story. She quickly receded into complete obscurity.

I am pleased and proud to bring May Darrach out of historical oblivion.

by Warren Shaw