A HISTORY OF GUIDE DOGS

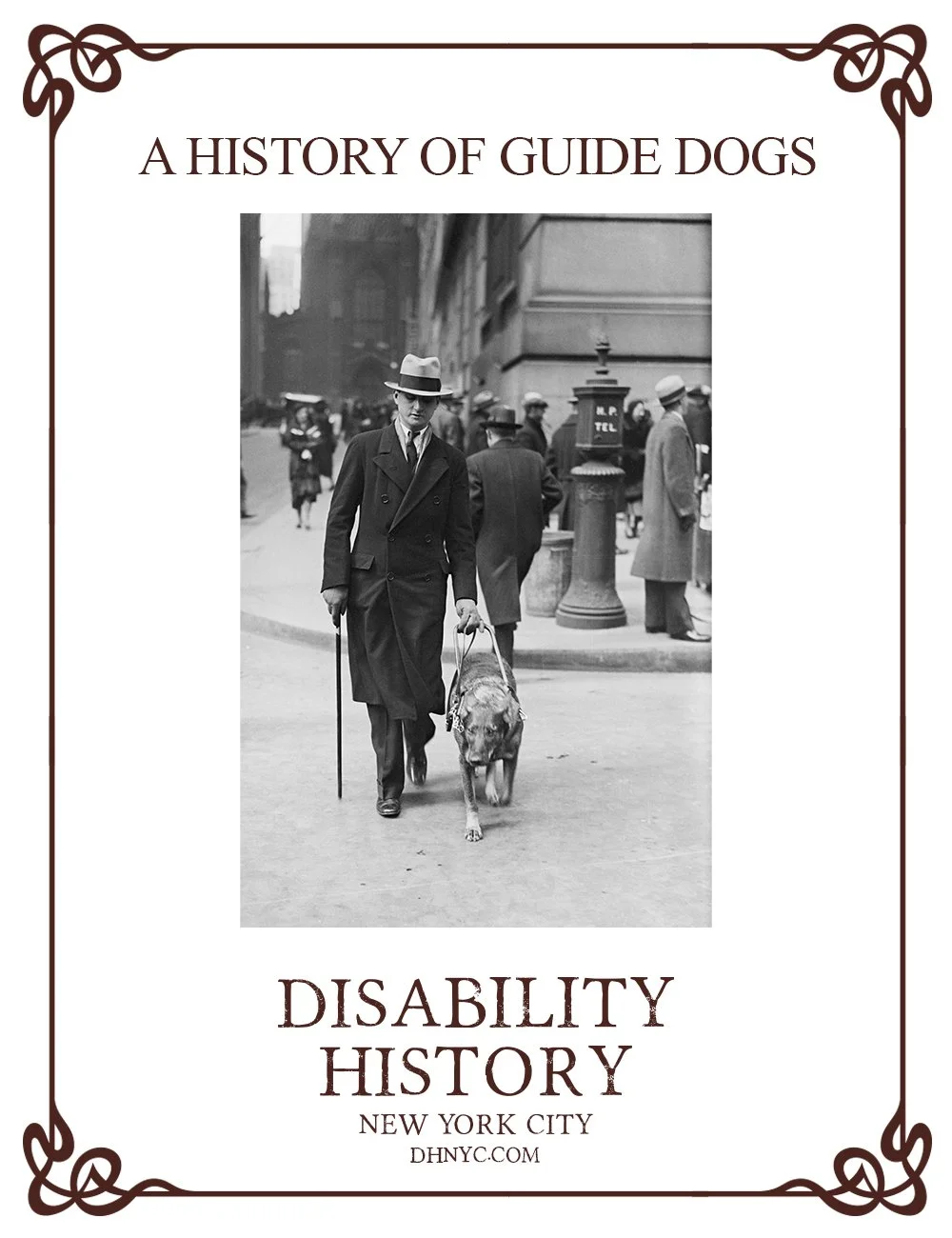

In Image No. 1 – Morris Frank with his guide dog Buddy, walking down Wall Street in the 1930s.

Here in the United States the use of guide dogs began only a few generations ago, but there is evidence of them dating back thousands of years—all the way back to ancient Pompeii, where an image of a blind man with a staff, apparently being guided by a small dog, was found on the wall of a house that survived being buried in ash--by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, in 79 A.D.

Starting in the late medieval era, the written and visual record repeatedly presents blind men (always men) with dogs. They are often shown as itinerant bards, musicians or storytellers. But most of the dogs seem too small to have served as defenders of their humans, and too small to have pulled people out of danger. And the dogs have flexible leashes, so they could only provide sort of general guidance as to direction--much more limited information than guide dogs can transmit today. Perhaps that’s why the humans in these old images are invariably shown carrying long staffs or canes.

The first inkling of the modern guide dog came in 1819, when a Viennese priest named Father Johann Wilhelm Klein proposed the use of specially trained canines. He also suggested that the connection between dog and human should be via a rigid leading stick instead of a flexible leash.

Remarkably, though, the story then goes dark for the next 97 years--until the First World War, when Germany’s German Shepherd Dog Society began training dogs to assist soldiers who’d suffered sight-related injuries in battle. Germans were already training dogs as messengers, so there were experienced instructors available, and by 1927 some 4000 people in Germany were using guide dogs.

This new concept in human-animal relationships came to the United States that same year, 1927, in the form of an article in the Saturday Evening Post, by Dorothy Harrison Eustis. Entitled “The Seeing Eye,” the article reported on Eustis’ observations of a guide dog training school in Potsdam Germany.

The article attracted quite a bit of attention, in particular from a 20 year-old blind man named Morris Frank, from Nashville, Tennessee. Frank wrote that he "would like to forward this work in this country.” Frank soon received a guide dog from Eustis, which he named Buddy, and in December 1928 Eustis and Frank launched the first guide dog training school in the USA, The Seeing Eye, in Frank’s hometown.

Frank became sort of an ambassador for the guide dog concept. He encountered some initial resistance. The director of the prestigious Perkins School for the Blind, Edward Allen, disparaged the idea in very over-the-top terms, as “a dirty little cur dragging a blind man along at the end of a string, the very index of incompetence and beggary.” But Allen later changed his mind, because these newfangled guide dogs were “so totally different from the ancient and medieval way.”

The next problem was breaking down social barriers against dogs in public places. By 1931, the Pennsylvania Railroad approved the use of guide dogs by visually disabled people on its trains. That same year, Eastern Airlines did the same, on a one-time-only basis, just for Morris Frank and Buddy. Eventually, federal, state and local policy united around allowing guide dogs in public places.

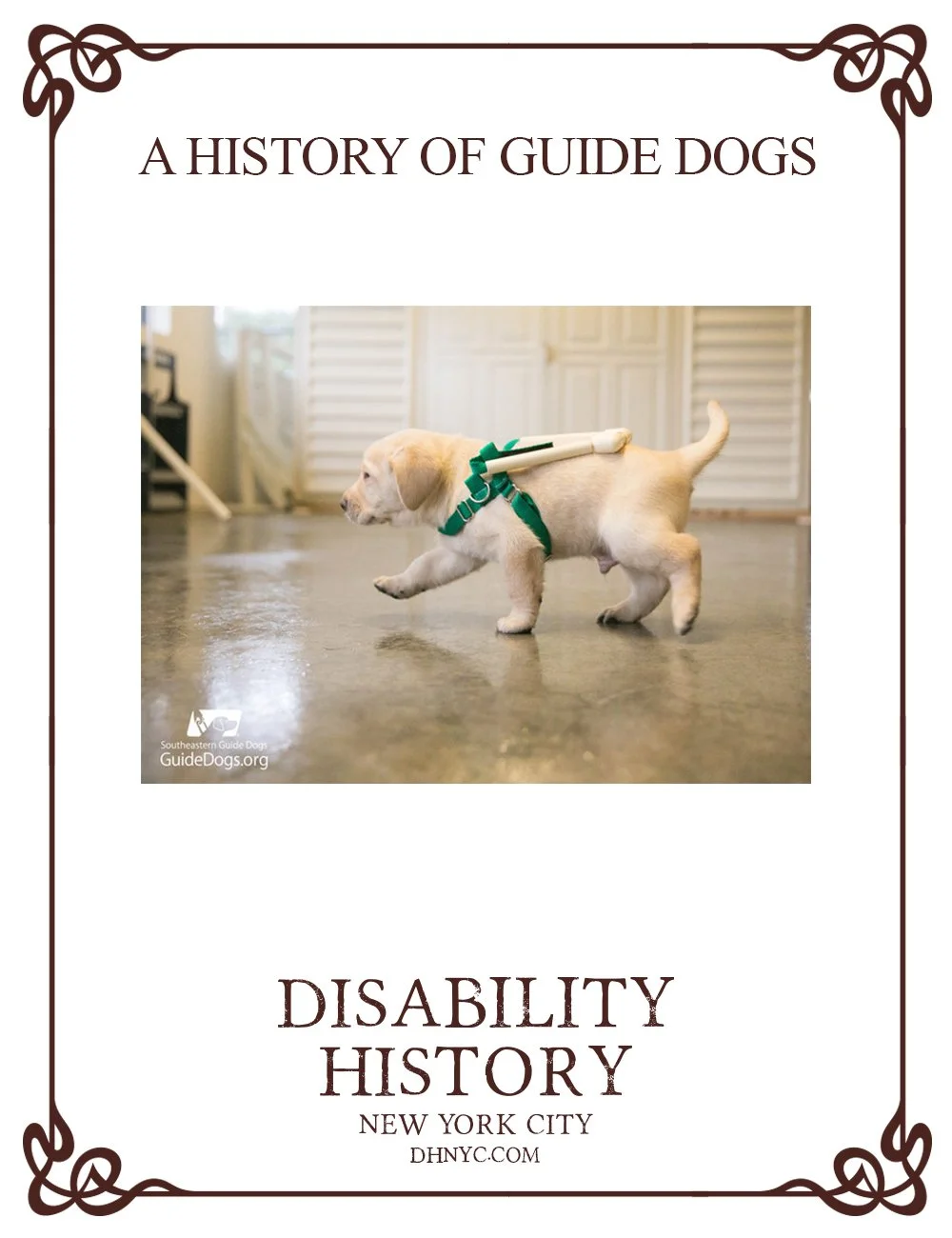

In Image No. 2 – A puppy training to be a guide dog.

Guide dog training begins when a canine candidate is around 18 or 20 months old, and the course of training runs four months. Most don’t finish the training process, because the demands are so exacting. They have to be able to stay unruffled and undistracted, completely focused on their human and their job, at all times and in all contexts. Successful student animals graduate to a life’s work that usually lasts about 8 to 10 years, usually with a single human being.

Finding guide instructors is another bottleneck. In its first 12 years, Seeing Eye was only able to train five new instructors. Today, aspiring teachers have to complete a three-year apprenticeship program. They get hands-on experience with training dogs--and with training their would-be handlers--under the supervision of experienced teachers, along with theoretical coursework and testing.

Interestingly (if not surprisingly), guide dog instruction was an all-male profession at first. Women were not hired as trainers until 1941, when a woman named Lois Merrihew began studying with Don Donaldson, then one of only ten guide dog trainers in the entire United States. Merrihew became the first female licensed guide dog trainer. And not only a trainer—Merrihew and Donaldson co-founded a training school called Guide Dogs for the Blind, which became an important provider of guide dogs for soldiers who lost their sight during the Second World War, and helped get federal legislation passed in 1947, which set standards and licensing requirements for both trainers and schools.

In 1996 there were 8000 graduates from ten established guide dog schools. As of 2010 there were about 10,000 guide dog teams in the United States, out of a legally blind population that’s around a million people. People who get a guide dog tend to go on using them—some 65% percent of canine graduates serve as successors to people whose previous dogs have retired.

Guide dogs are unique in the complexity and immediacy of the information they’re called upon to convey, and in the composure they have to maintain in all sorts of environments. It is a most refined, dare I say civilized, relationship.

Note: A version of this entry appeared in Able News, ablenews.com

by Warren Shaw